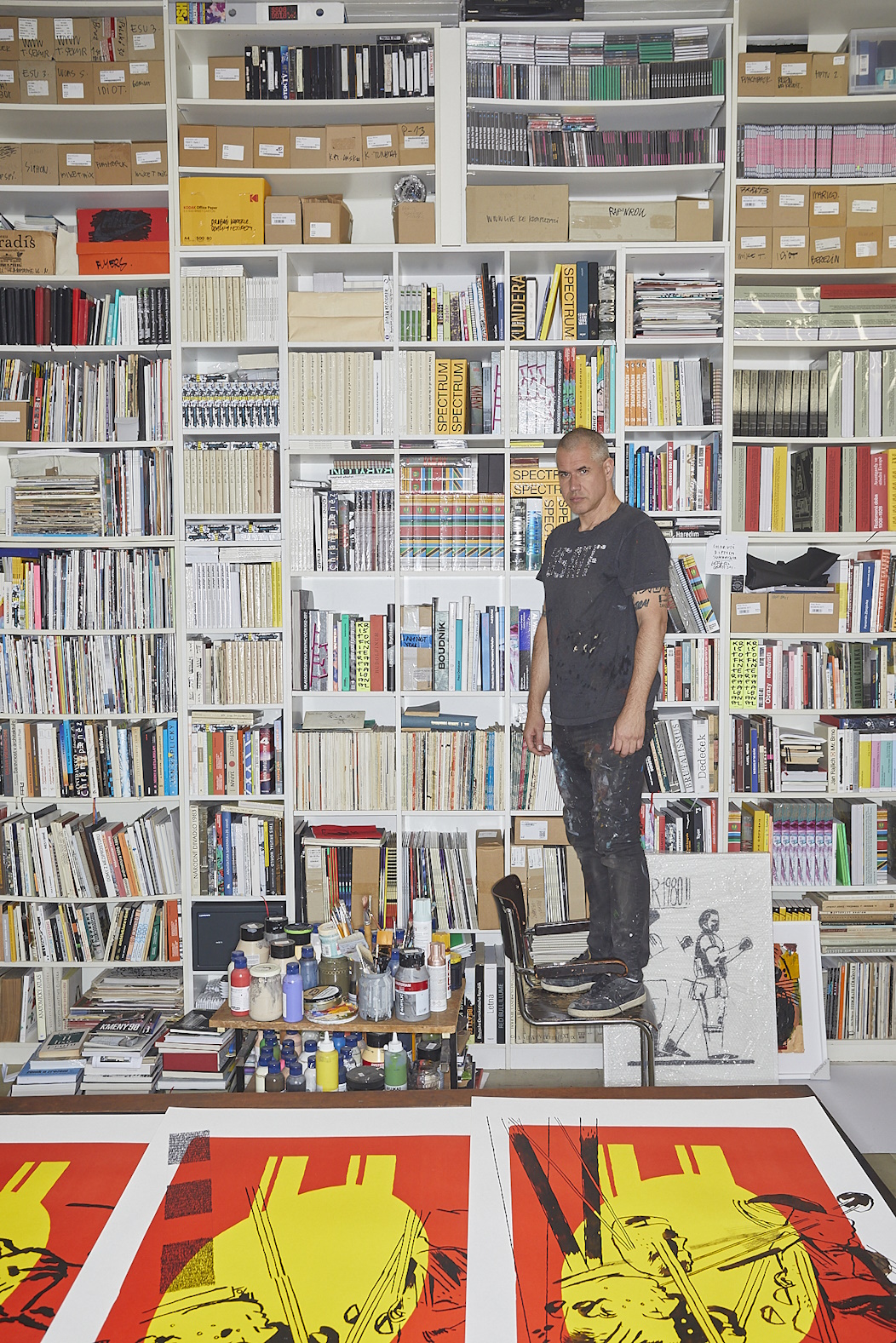

Vladimir 518 is a standout figure in the Czech art scene. He’s a rapper, illustrator, graphic designer, painter, publisher, and a well-informed fan of architecture. When he speaks, it’s always with flair and style, often combining both. During a break in his spring tour with Penerů strýčka Homeboye, who he’s still touring with around the Czech Republic, he stopped by his favorite spot in Vinohrady, the Kaaba café, to chat about his paintings inspired by physical activity. I didn’t realize just how closely Vladimir’s exploration of human animality, a major theme in his work, aligns with the themes of this magazine, and how it connects sports and art.

MT: You once said, "I compensate for the stress after concerts with sports." Is that still true?

V518: If we’re talking about the relationship between work and movement, it’s turned out well. The universe gave me a negative experience that I managed to turn to my advantage. I had a herniated disc in two places. For a quarter of a year, I could barely move, walk, or perform a concert. I remember giving myself the task of holding ten breaths on my back. For six months, I couldn’t do it. Facing such extreme pain gave me a new motivation in life. I exercise every day; I never would have thought I could do it. Simply because I was raised on many negative role models: writers, painters, musicians…

„

Vždycky jsem vedle muziky dělal ilustrace, plakáty, experimentální scénografie a audiovizuální umění, ale cítil jsem, že se potřebuju posunout do volné tvorby. Že je to nevyhnutelné. A tak jsem se vrátil do ateliéru v MeetFactory a už jsem nevylezl.

MT: …with zero regard for lifestyle.

V518: Yes, nobody talks about a healthy lifestyle; they deal with other issues. The disruption of the soul and complexities of existence are more attractive topics in art than how to keep the body functioning long-term.

MT: But there’s exercising and then there’s exercising. A lot of people end up hurting themselves.

V518: When my physiotherapist told me I had to listen to my body, I was skeptical and suspicious; it smelled of esotericism. However, if you're struck by such pain, you’ll try anything. I found out that the person was right. My body asked for a few specific exercises, which I still do because I feel they help.

.jpg)

MT: Two years ago, you undertook a social project where you walked along the D1 highway from Prague to Brno. You were interested in an area designated for no one. I think it must have been quite a physical experience for you, a real long-distance trek.

V518: I prepared for it for quite a while, carrying thirty-five kilos on my back: sketchbook, camera, hard drives, chargers—all to document that crazy journey. It wasn’t easy; you’re constantly pushing through underbrush, crossing ditches, and climbing fences in a crazy terrain. It’s not like walking the Camino de Santiago. It’s a territory hostile to humans, or any beings really. Dust, noise, stress, and absurdly difficult movement. On the other hand, I like challenges and have a positive relationship with movement. I’ve been into sports my whole life—I love hiking, running, cycling, swimming.

MT: One of your older albums is titled Ultra! Ultra!. How should we interpret that term? As going all out in everything?

V518: I tend to approach life with an extreme attitude. If I trained like I work on my projects, I’d be in the grind like a professional athlete. I don’t have that, but I want to be honest.

MT: In the first issue of Sport in Art, we included a sports soundtrack featuring the track “Trénink” by PSH. What does training mean to you? Is it about drills and mechanical work, or a challenge and a space for improvement?

V518: I like that training makes you leave yourself behind. Your awareness dissolves; there’s a certain transcendence. Training puts you into a regular rhythm; it’s a process with order. If I relate it to architecture, I recall my favorite text, a textual and visual manifesto by Hans Hollein, a postmodern and immensely important Austrian architect. It’s called Alles ist Architektur and discusses the meaning of the spatiotemporal grid in our existence, the meaning of repetition, regularity, and construction. We all move within that grid, and it’s good to surrender to it sometimes. Training allows that. Drills are a form of transcending oneself, surrendering to rhythm; it’s almost a shamanic ritual. When I was banned from running due to my back, I started swimming, and forty laps can take you quite deep into yourself.

MT: You used to play basketball competitively. How far did you get?

V518: During my puberty in the '90s, I went through training drills in a SK Hvězda Vinohrady jersey in the gym on Žitná Street. I was tall and had a talent for movement; it seemed natural. I didn’t have trouble existing in a team, but I couldn’t establish a positive relationship with the coaches.

MT: Issues with authority?

V518: I’ve had that for a long time. When someone isn’t a natural authority and imposes dominance through the system, I have a big problem. On the other hand, if I naturally admire someone and they don’t impose themselves with force but with what they truly know or can do, I’m willing to go to great lengths for them.

MT: As a complement to our conversation, you chose paintings related to sports or at least physical contact. There are quite a few. What does sport actually say about us?

V518: To put it very briefly, in my drawings, paintings, or objects, I often search for the ancient beast within humans. Sport is a rare, surviving archetype of animality, and that’s what makes it valuable. As humanity, we should value that we’ve turned life-and-death struggles into theatrical encounters. We’ve stopped mutilating and killing each other and instead dress up in costumes and go to fight on a well-lit stage before filled stands. There we perform a show with no predetermined outcome. Usually, that is. It reminds me of Zdeněk Sýkora and his systems. You have two halves of the field, white lines, colored jerseys, a round object, and then you throw in some dice; let the events unfold. Sýkora did this; he combined systems and randomness in his works.

MT: Are you interested in who wins in sports?

V518: Awards, victories, medals—they’re just stamps for alpha males. Ran the fastest, shot the best, threw the farthest, or had fantastic technique and knocked out the opponent. I respect that; it’s part of it. But honestly, I view it from a greater distance, focusing more on the composition of bodies and trying to perceive the emotions driving everything. Those who lose are just as interesting to me as those who win.

MT: Because everyone puts something ancient into the fight…

V518: Animality is important under certain conditions; otherwise, we’d only have rules and order, too sterile a civilization. Finding the beast within us is crucial because it reminds us that we are part of evolution, nature, and history. I love observing animals, my dog, birds in the park; I try to see myself in them. And I find myself there. We stretch in the sun like cats, children snuggle like animal cubs. Finding your own animality is magical, and besides connecting with the world, it can also drive that competitive spirit in sports.

MT: Do you support anyone?

V518: As a kid, I was an ultra-fan of Slavia. My dad was a Spartak fan, and I followed my grandfather’s faith. So, we had a bit of a family issue. Back then, the old Eden still stood; I even went to training sessions, kept notebooks with signed photos, and had a photo of Slavia with my two heroes, Ivo Knoflíček and Luboš Kubík, above my bed. When they fled the country before the revolution, it hit me hard. I remember coming home from school, my dad solemnly telling me, and then drawing dollars over the players on the poster, as if they left for money. I was a little kid and didn’t fully grasp that we lived in a cage. At that time, I cried about it, felt it as a betrayal, and stopped supporting football. I turned to culture.

MT: Orion, your friend and bandmate from PSH, is a passionate fan of Bohemka. That’s known. Do you have any understanding for him?

V518: Definitely, Bohemka is an outsider club in a way, but there’s something sympathetic about it because it’s not macho. When we’re driving to a concert, Orion watches the game on his laptop, Bohemka is losing two-nil, but he’s happy because it could have been worse. That’s a lifestyle. Bohemka fans are people who can accept defeat and failure and find joy in the little things, like one good shot. Supporting Sparta means being an alpha male who must always be first and best; anything less is seen as a loss. Learning to support Bohemka means you can overcome anything. It’s a training of hope.

MT: Orion, your friend and bandmate from PSH, is a passionate fan of Bohemka. That’s known. Do you have any understanding for him?

V518: Definitely, Bohemka is an outsider club in a way, but there’s something sympathetic about it because it’s not macho. When we’re driving to a concert, Orion watches the game on his laptop, Bohemka is losing two-nil, but he’s happy because it could have been worse. That’s a lifestyle. Bohemka fans are people who can accept defeat and failure and find joy in the little things, like one good shot. Supporting Sparta means being an alpha male who must always be first and best; anything less is seen as a loss. Learning to support Bohemka means you can overcome anything. It’s a training of hope.