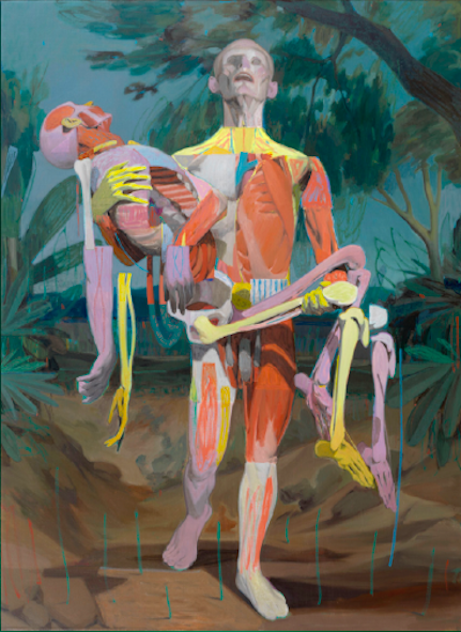

How long is the journey from flipping through mom's books about Goya to becoming one of the leading Czech artists? You can find out in an interview with Lubomír Typlt, who not only paints but also avidly collects art. Besides that, he is currently preparing an exhibition in Prague, both for himself and for the contemporary Spanish painter Aryz. However, Lubomír Typlt's creativity extends far beyond just the canvas, as we can see, for example, at concerts of the band WWW Neurobeat, where he has been working as a lyricist since the nineties. These areas intertwine more than meets the eye at first glance.

We met at the Art Grand Slam exhibition: Inside the Movement at Prague's SmetanaQ Gallery, which presents two of his large-format paintings. The exhibition is open until March 17th.

Tell us something about how you got into painting. I know you studied illustration at UMPRUM, painting at FaVU, and then in Düsseldorf. But how did it all start?

In the 1990s, painting was a medium that didn't have an easy ride. For me, it was nice to be in Düsseldorf at that time, at the academy where artists like Gerhard Richter studied. The environment there was supportive of painting, and there wasn't the same struggle with the proclamation that painting was dead, which was a slogan that everyone kept repeating here. How can you develop in an environment that from the start tells you to do something else? For that reason, I think I made a very sensible decision. Nowadays, things have changed again, and often those who criticized painting back then are now riding the wave of renewed interest in painting. They've changed their tune, and I find that a bit amusing.

.jpg)

Painting has been enjoying increasing interest in recent years.

Painting has been on the rise for at least the last 10 years. With the emergence of artists like Neo Rauch or Daniel Richter in Germany, figuration has returned to the forefront of people's attention, including galleries and, most importantly, collectors. This trend has also reached here. When I decided to study in Germany, it was partly for this reason—to avoid replicating the Czech model of "when something successful is happening elsewhere, let's start doing it here too."

When I go back to the beginning, did you always know you wanted to paint?

My mom is an amateur painter, and we had books about Goya, Repin, and Shishkin at home. My brother and I would look through them as kids, and it greatly influenced me. Even in primary school, I knew I wanted to be a painter and I went to Hollarka, then to UMPRUM for illustration. I didn't have confidence in painting because I didn't understand the system and the academy was de facto unsympathetic to me through Knížák. I didn't have confidence in painting because I didn't understand the system, and the academy, through Knížák, was essentially unsympathetic to me. However, as a fourteen-year-old boy, I admired Načeradský; he was simply a god to me. When Šalamoun at UMPRUM asked if anyone wanted to do an exchange program with Načeradský at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno, my hand shot up faster than my brain could react. At that time, we already had WWW Neurobeat, which was doing well, so I was hesitant, but my passion for art was so great that I ended up going to Brno.

What was he like?

Načeradský and I hit it off. He was incredibly impulsive and decisive; what he thought, he said. Today, I can say that we liked each other. When he was dying, he gave me his paints.

„

On his deathbed, he told his family that he wanted me to have his paints, and I cried.

Studying under him gave me a lot. I still feel like I owe him something, which I try to repay. Načeradský was a key figure, and I hope he will be recognized soon; I'm doing what I can to make that happen.

So you didn't stay there for long and went to Germany.

Even when I was with him, I was eyeing Germany. I was 20, the borders were open, and everyone wanted to see Western art. I went to Berlin, where there was a retrospective exhibition of Georg Baselitz and Lovis Corinth, and I was just blown away. For me, influential painters were like Kubišta and others who never painted for commercial purposes. Suddenly, in Germany, I saw that the model of unpopular art was normal. That gave me a huge push, and I wanted to study there. I was only with Načeradský for a year; then I went to the academy in Düsseldorf. It was quite a twist. Back then, there was no internet, so I didn't really know who taught at the academy. I mainly knew about Markus Lüpertz and Magdalena Jetelová, who told me to go there during the final exams. But at that time, I only had about five paintings; I went straight from illustration to Načeradský, so I didn't have a big portfolio, and the paintings I presented were dead cats. I was pretty nervous, but I met Lüpertz in the hallway, and when I showed him my work, he said it was good and that I could come as a visiting student. So, I started with him, then went to Gerhard Merz, and ended up with A.R. Penck. Penck was amazing, very humane, and the environment there was great; he had a tremendous perspective.

We are at the Art Grand Slam exhibition, surrounded by artworks inspired by movement and sports. What was your first thought when Petr Vaňous approached you to participate in the exhibition?

It didn't surprise me all that much. I understand the connection with bicycles, although it's a bit more complicated. I find it quite amusing that these paintings resonate with people who ride bicycles, even elite cyclists. One of those paintings is even owned by Mr. Kasper, who has a luxury racing bike standing next to it. It's a bit funny to me because I paint those bikes with a slightly different background in mind.

This motif often recurs in your work. You even transformed it into an object. Would you like to reveal what stands behind it, or do we leave this metaphor open for the viewers?

Around 1998, I was searching for what I wanted to paint. I was very interested in conceptual art and ready-mades at that time. I'm a big fan of Duchamp. At the same time, I love painting, so it was just about figuring out how to combine the two. I assembled objects back then. I cleaned up an old bike and hung funnels on it. That was actually the first painting, and I've been returning to the idea of the bike more or less throughout my entire creative career. The wheels on that bicycle were then replaced with barrels. One day, I was drawing in the studio, trying to come up with a new composition, and suddenly umbrellas, which I painted around 2015, found their way to that bike. I realized that when you look at the umbrella, it's an octagon. Reduce that, and suddenly it works like a wheel. Of course, I also approached it through art history. But a new form emerged that works well.

What do you think about the concept of exhibitions and competitions by the Sport in Art platform?

I think the concept actually works very well. If we remember the Futurists, with Goncharova's Cyclist. These are all strong themes. The analysis of movement is present in the Futurists. And if someone manages to take a slightly different approach to that movement, then those artifacts can work quite well. The emphasis doesn't even have to be solely on sports.

When we talk about sports, apparently, you don't have the best memory of it. You smashed your lip while playing sports and couldn't be a trumpet player afterwards.

That's true, it happened once when we were at Ondřej Anděra's, the singer of WWW Neurobeat, at home. A Roma guy who was quite buff sang with us for a few concerts back then. He did a push-up with clapping, which I had to try too. Only I didn't manage it. So, I ended up lying on the tiles with a smashed lip. I destroyed the embouchure on the trumpet, and it was serious; I really couldn't play afterward, no matter what I did, I couldn't hit the high notes. The scar hardened, and the lip got tired. It was kind of funny back then, but I paid quite a price for it.

You're currently preparing an exhibition for the Spanish muralist Aryz. What about him appealed to you that made you decide to bring him to the Czech Republic?

When I spoke about my beginnings, I hinted that I grew up with Goya, but also with Velasquez; overall, I'm quite familiar with Spanish art, and I deeply respect it. Thanks to Instagram, I discovered Aryz, and I liked what he was doing. I followed him for about two years. I have a circle of friends with whom we exchange art tips we like, and one friend, collector Martin Procházka, wrote to Aryz asking for his price list. Then he asked me if I'd like to go to Aryz's studio with him, which I immediately agreed to. Even though I had studied his work already, his paintings completely captivated me in person.

The quality of his work is very high. We approached him at a time when it was still possible, and I offered him the opportunity to exhibit at our venue. It took about four months for him to confirm. Before Christmas, he came, visited Villa Pellé, and we signed a collaboration agreement. I think it will be a big event in the Czech Republic.

Don't you feel like owning any of his works yourself?

I've bought one painting from him. I believe it's one of the best paintings he has created so far. I have a lot of faith in his work, and I think the exhibition will be great. I want to show Czech audiences painting at its highest quality.

You sell your paintings to collectors, but you also collect yourself. What do you have in your collection, for example?

You could say I've been a collector for about 15 years now, and I've always hit the mark. I've always collected pieces from artists who weren't yet recognized. For example, Honza Poupě once approached me to be his opponent. I declined with thanks because I didn't have the time, but when he showed me his pieces in his studio, I was amazed. I ended up buying his entire diploma work from him. Today, after ten years, they're iconic paintings. Honza wanted to work, wanted to sell, wanted to make a living from painting. He recently auctioned off his painting at Kodl's for 780 thousand. I'm happy when artists succeed.

„

There are top-notch painters out there, and when I can, I gladly buy their paintings, especially when they need it.

When I think back to the existential problems I had at the beginning... I didn't start selling until I was thirty-five. And the collectors who supported me back then are now very close friends of mine.

It's a bit risky, though.

That's what I enjoy about it. You're buying a piece that doesn't yet have a market value, so you can't immediately rush out and resell it. The artist needs to develop, and we certainly don't want painters, like Kubišta back then, dying of hunger. Or how Alén Diviš ended up? That's a disaster. I might have a bit of an advantage being a painter myself, and perhaps I understand better what's good and what's bad, so if I can alert someone to good art, I'm happy to do it.

In one of the European states, there's reportedly regular financial support for artists from the government.

That's a road to hell. This system was in place in the Netherlands, and it ended up with the Netherlands having warehouses full of worthless paintings. Artists were getting a pension for nothing, and it didn't help their development at all. You have to justify it somehow. People can't come out of art school and then receive a salary. Those subsidies will destroy the competitive environment. Even in the Netherlands, it was proven that it was the wrong path.

I recognize that I truly like a piece of art usually based on the fact that it starts to affect me, my body starts to vibrate, and I feel some excitement, a kick. Do you have a similar experience that helps you decide whether to add a piece to your collection?

Certainly, these emotional reactions are crucial. When I see a truly quality piece of artwork, it has a significant impact on me and can truly inspire me. For me, it's important for a painting to have power and to conceal some deeper meaning behind it. For instance, Gerhard Richter says that art is a form of faith. I believe that for art enthusiasts, artists are true gods. Just imagine the effect Picasso's paintings have on people...

I remember when I first saw your paintings. It was at the ARS Gallery, and I stayed there for quite a while. I don't think I had ever experienced such a surge of energy from paintings live before.

That really pleases me; that exhibition was quite significant at the time. It was the first exhibition arranged for me by such a renowned gallery. It happened during my studies with Načeradský when Mr. Josef Chloupek, the gallery owner, visited our school. He had a great eye for talent and exhibited truly remarkable artists. I was just a young student back then, who had painted only a few things, mainly dead cats and birds. But he approached me and said he wanted to exhibit my work. However, this angered some of the older artists at the school, and they retaliated against me in various ways. For instance, I was one of the few who received a low grade for my diploma work, which prevented me from applying for a scholarship in Germany and complicated many things for me. I struggled with the resentment of some artists here for quite a long time.

But I believe that if someone envies you or tries to trip you up, it won't stop you. It'll only make you stronger. I then went ahead like a steamroller and worked hard on myself. Because if you want to break through, you have to fight, even if nobody's pampering you.

Obstacles can really fire up a person.

Absolutely. Take Marcus Lüpertz, for example, who served as rector at the Düsseldorf Academy for twenty-five years; he also studied there himself. Someone once told him to take his few unsuccessful works and leave, but he didn't let that discourage him. Twenty years later, he returned as rector and was in charge.

„

Artists must be determined. Especially when they are young, they must be able to define themselves and proudly present their intellectual sphere to the world, which they are processing.

Do you think that Czech galleries and collectors adequately support artists and purchase their works?

There are quite a few collectors in the Czech Republic, historically even. Large collections have always been present here, and often even big foreign names ended up here. When Edvard Munch exhibited here once, the sculptor Stanislav Sucharda bought one of his pieces. Artists have an eye for that. There have been great international exhibitions here. When I was guiding one of the most important gallery owners of the 1980s, Michael Werner, at the National Gallery, he told me that we have better collections than in Cologne. We have Picasso and such here, but no one knows about it.

And what about your collection, do you plan to hold an exhibition? It would be interesting to peek into your taste.

Perhaps I won't be able to avoid it eventually. Whenever I tell someone the names I have in my collection, they are usually quite surprised. For example, Alexander Tinei acquired his work at a time when his art wasn't in such high demand yet. I always get really excited about something. You quickly forget about the money you spent on it at that moment. And then, when those artists shoot up like Tinei is doing right now, you wonder how it's possible that so few people saw it back then. I recently made an excellent catch. German painter Simone Haack, whom I invited to a joint exhibition at DSC Gallery during Covid. People were a bit hesitant about what she was doing. However, her work is skyrocketing now. Just a moment ago, I bought a painting from Remus Grecu.

Do you think Czech artists know how to set their prices?

The price is determined by the market. Surprisingly, I bought Greco's work for a lower price than the usual prices of some local artists here. Yet Remus Greco is a bigger name on a European scale. It's important not to confuse the price of a painting with its quality; that would be a mistake. The price of a painting changes over time.

Do you think an artist can be harmed when represented by a particular gallery?

It can only harm them if the gallery is bad. If they fall into the wrong hands, it can ruin them. The art market is really complex for laypeople. It can be a way up, but also down, and the artist has to navigate that, they have to know where they want to exhibit and where not.

Have you ever made a misstep?

I've always gathered information from people who are active in the art market. But yes, once, a certain auction house bought fifteen paintings from me, claiming they would go into their collection, but instead, they immediately went to market. It took me three years to sort that out. Some people are completely unscrupulous; you're just a product to them. But now I know better, and I've advised many young artists to be careful. When someone breaks your price right at the beginning, it's hard to recover.

You also have a successful music project called WWW Neurobeat, which was formed back in the nineties. Your style is completely unique in the Czech scene. You're planning concerts again, which is great news for us fans.

Ondřej and I are currently on a perfect wave, working on a new album. I'm excited about it. We've known each other since we were about fifteen, sometimes it feels like a very long marriage. But I was just listening to it in the studio and I thought to myself, I'm really glad to be part of it and that we've endured. It's hard work, a lot of time, and a big responsibility. When you set the bar high, it's easy to fall below it. Behind it is a lot of work, but I'm enjoying it now.

I see a certain parallel there; the music of WWW Neurobeat, much like your paintings, is full of vibrant energy that sometimes gives off a slightly unsettling impression.

That sense of unsettlement is important to me because then the painting starts to communicate with you. The art that I've always admired has never really been to my taste. For example, I like the underrated painter František Janoušek. His paintings are raw, without the societal layers that were fashionable at the time. They reveal the essence. The art that speaks to me shows people in a somewhat unflattering light. For those in the conventional consumerist society, with their fancy cars and handbags, my paintings might not sit well, like a bitter coffee. And that's what I find enjoyable.

The titles of your paintings are excerpts from WWW Neurobeat song lyrics, is that so?

Often that's the case. The lyrics, like the paintings, are somewhat Dadaist. And I enjoy how that transfers onto the canvas, even though the title doesn't actually help you understand the painting at all. Yet, there's often that proximity, but it's more of a poetic closeness. You need to be in a certain mood to immerse yourself in it. Lately, I've noticed that fans of WWW Neurobeat are starting to attend my exhibitions, which makes me incredibly happy. It's like an expansion of space.

What are you listening to while you paint?

I listen to a wide range of things. I even like good pop music. When I hear Dua Lipa's voice, it just gets me going. When I need a real kick, it's Zardonic, which is electronic bass metal, very intense. I still listen to bands I grew up with, like Nine Inch Nails, which was a big influence for me in terms of music independence and expression. Or Rage Against the Machine.

And what are you currently working on?

Right now, I'm working on an exhibition at DSC Gallery. We have a great curator, Domenico de Chirico. I'll be exhibiting alongside Adam Štech. It's clear that he comes from completely different cultural backgrounds, but he reacted very positively to our work, which is a big boost for me, knowing that the painting communicates even without the same language. That's the great advantage of paintings. Someone from Milan can perfectly understand my carousel. I recently had a major exhibition in Bratislava, and it was great to observe what my paintings were doing to those people. They evoke emotions, and that's great.

Thank you very much for the interview.

You can see Lubomír Typlt's paintings at the exhibition Art Grand Slam: Inside the Movement until March 17th at the SmetanaQ Gallery. Established names of the contemporary Czech art scene represented at the exhibition include Michael Rittstein, Milena Dopitová, Dalibor David, Paulina Skavová, Michal Cimala, Pavel Šmíd, Alena Anderlová, Jakub Janovský, and Jitka Petrášová. Curator Petr Vaňous also selected three names from the Open Call, including works by Veronika Čechmánková, Lukáš Slavický, and the authorial duo Tereza Sikorová and Tomáš Moravanský from INSTITUT INSTITUT.

Look at all the works from the exhibition.

About Jiří Načeradský, theorist and curator Petr Volf has also written. You can find the article 'Wolf's Territory: 1967, the Year Jiří Načeradský Became a Legend' here.